(Urdu: محمد طاہر القادری; born 19 February 1951) is a Pakistani–Canadian Islamic scholar and former politician who founded Minhaj-ul-Quran International and Pakistan Awami Tehreek. He was also a professor of international constitutional law at the University of the Punjab. Qadri is also the founding chairman of various sub- organisations of Minhaj-ul-Quran International. He has authored 1000 works, out of which 550 are published books, including an "eight-volume, 7,000-page Qur’anic Encyclopedia in English covering all 6,000-plus verses of the Koran." He has delivered over 6000 lectures and has been teaching subjects such as Islamic jurisprudence, theology, Sufism, Islamic philosophy, law, Islamic politics, hadith, Seerah, and many other traditional sciences. more information about A Profile of Shaykh-ul-Islam Dr Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri

“The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám” is a long lyric poem in quatrains (four-line stanzas) of iambic pentameter, with a rhyme scheme of AABA. Translated by Edward Fitzgerald from a manuscript of Persian verse attributed to Omar Khayyam, a 12th-century Persian mathematician and philosopher, “The Rubaiyat” contains pithy observations on complex subjects such as love, death, and the existence of God and an afterlife.

When “The Rubaiyat” was first published in March 1859, it received little attention. Fitzgerald, a friend of Victorian poets like Alfred Tennyson (1809-1902), was considered only a minor literary figure at the time. However, poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) discovered the poem in 1860 and played a significant role in popularizing it. From thereon, “The Rubaiyat” had a meteoric rise in popularity, becoming one of the most-quoted poems in English by the early 20th century. It is useful to consider Fitzgerald’s “The Rubaiyat” partly as a work of English literature, since his translation is extremely free and creative. Some critics consider “The Rubaiyat” as a standalone poem inspired by the original Persian verse, rather than a transcreation. Fitzgerald revised “The Rubaiyat” four times after its first publication, so that there exist five published editions of the poem. This study guide uses the first edition. Many of the changes Fitzgerald introduced in subsequent editions are quite significant, as can be seen in this comparison of two versions of Verse 1:

First edition

Awake! for Morning in the Bowl of Night

Has flung the Stone that puts the Stars to Flight:

And Lo! the Hunter of the East has caught

The Sultan’s Turret in a Noose of Light.

Fifth edition

WAKE! For the Sun, who scatter’d into flight

The Stars before him from the Field of Night,

Drives Night along with them from Heav’n, and strikes

The Sultan’s Turret with a Shaft of Light.

Poet Biography

Omar Khayyam (full Arabic name Ghiyāth al-Dīn Abū al-Fatḥ ʿUmar ibn Ibrāhīm al-Nīsābūrī al-Khayyāmī; 1048-1131 AD) was a renaissance man long before the dawn of the European renaissance: an expert in subjects as diverse as mathematics, law, and philosophy. Khayyam (the family name literally meaning “tent-maker”) was born in Naishapur, in northeastern Persia, around the time when the Seljuk Turk (a central Asian tribe) dynasty began to rule the region. When he was 20, Khayyam moved to the great city of Samarkand, now in Uzbekistan, for work and further scholarship. It is in Samarkand that he wrote some of his greatest treatises on algebra.

Prodigiously intelligent and reserved in temperament, Khayyam was an agnostic who chafed under the orthodox religious state the Seljuk Turks were beginning to impose in Persia. However, Khayyam did enjoy court patronage from time to time, which enabled him to finish many significant works. Among his other scientific achievements, Khayyam discovered a geometrical method of solving cubic equations by intersecting a parabola with a circle, and helped design the Jalali calendar, a very advanced solar calendar, a modified version of which is still in use in Iran. Khayyam is believed to have married and had children; beyond this, not much is known of his personal life.

Though Khayyam was famous for his erudition in his day, very little was known about his poetry. Some scholars speculate that he did not dare to make his poetry public at the time, since it contained heretical (dissenting from established religious belief) themes. However, these claims are unproven. Verses under Khayyam’s name began to appear in the oral tradition only much after his death. In the coming centuries, there grew a tradition of attributing verses to Khayyam, especially those that tackled nihilistic philosophy, a rejection of the afterlife, and an emphasis on living in the moment. It is unclear if the historical Omar Khayyam wrote all or most of these verses, or if they were even written by any one single poet.

Edward Fitzgerald (1809-1883) was an English writer and poet. A member of what grew to be one of England’s most wealthy families of the time, Fitzgerald was educated at Cambridge university. Single for most of his life, Fitzgerald married Lucy Barton, daughter of the Quaker poet Bernard Barton, in 1856. However, the couple separated a few months after the wedding.

https://www.supersummary.com/the-rubaiyat-of-omar-khayyam/summary/

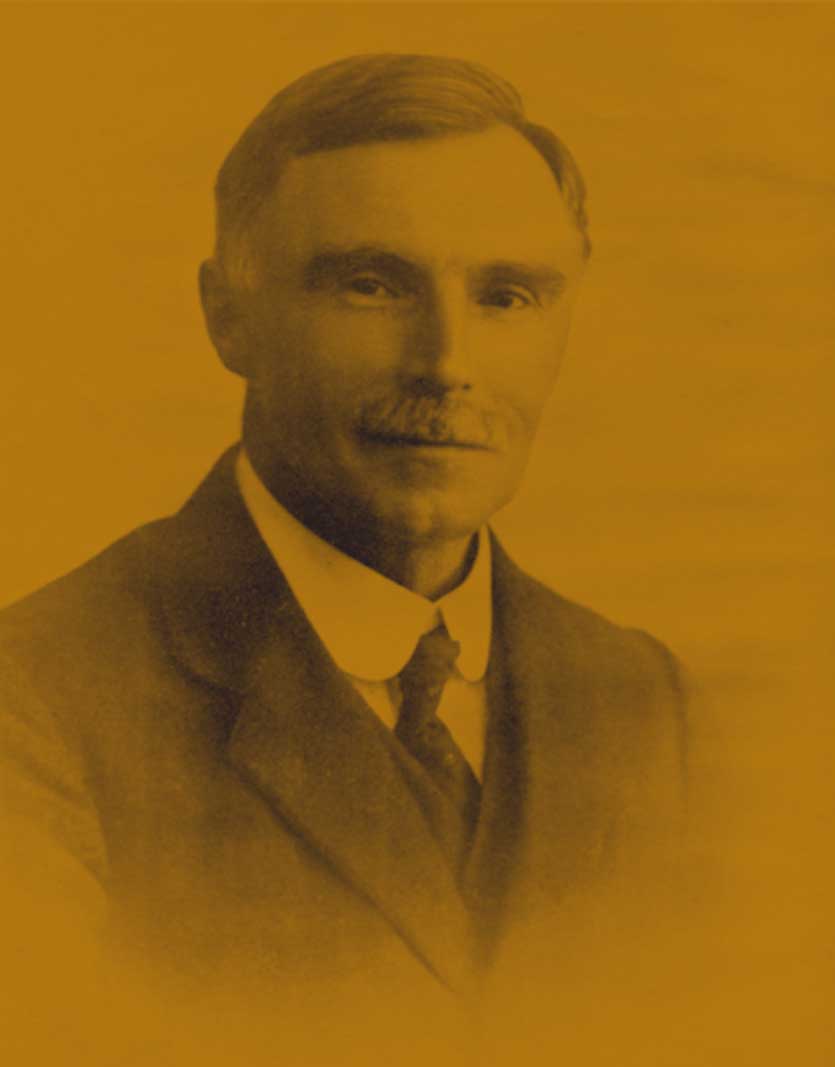

(born Aug. 18, 1868, Keighley, Yorkshire, Eng.—died Aug. 27, 1945, Chester, Cheshire), English orientalist who exercised a lasting influence on Islāmic studies. Educated at Aberdeen University and the University of Cambridge, Nicholson was lecturer in Persian (1902–26) and Sir Thomas Adams professor of Arabic (1926–33) at Cambridge. He was a leading scholar in Islāmic literature and mysticism. His Literary History of the Arabs (1907) remains a standard work on that subject in English; while his many text editions and translations of Ṣūfī writings, culminating in his eight-volume Mathnawi of Jalalu’ddin Rumi (1925–40), eminently advanced the study of Muslim mystics. He combined exact scholarship with notable literary gifts; some of his versions of Arabic and Persian poetry entitle him to be considered a poet in his own right. His profound understanding of Islām and of the Muslim peoples was the more remarkable in that he never traveled outside Europe. A shy and retiring man, he proved himself an inspiring teacher and an original thinker.

Reynold Alleyne Nicholson (1868-1945), was the greatest Rumi scholar in the English language. He was a professor for many years at Cambridge Universtiy, in England. He dedicated his life to the study of Islamic mysticism and was able to study and translate major sufi texts in Arabic, Persian, and Ottoman Turkish. That a Western scholar of "the first rank" dedicated much of his life to the study and translation of Rumi's poetry was very fortunate.

His monumental achievement was his work on Rumi's Masnavi (done in eight volumes, published between 1925-1940). He produced the first critical Persian

edition of Rumi's Masnavi, the first full translation of it into English, and the first commentary on the entire work in English. This work has been highly influential in the field of Rumi studies, world-wide. His critical Persian text has been re-printed many times in Iran and his commentary has been so highly respected there, that it has been translated into Persian (by Hasan Lâhûtî, 1995).

Nicholson also produced two volumes which condensed his work on the Masnavi and which were aimed at the popular level: "Tales of Mystic Meaning" (1931) and "Rumi: Poet and Mystic" (1950).

His earliest translations of selected ghazals from Rumi's Divan ("Selected Poems from the Díváni Shamsi Tabríz," 1898) has been superceded by A. J. Arberry's translations ("Mystical Poems of Rumi," 1968; "Mystical Poems of Rumi: Second Selection," 1979), in that Arberry used a superior edition of the Divan (done by Foruzanfar). Arberry re-translated all of the ghazals previously translated Nicholson (his teacher and predecessor at Cambridge University) based on the

superior edition, minus seven ghazals which were not in the earliest manuscripts of the Divan (and therefore are no longer considered by scholars to be

authentic Rumi poems (Nicholson's numbers IV, VIII, XII, XVII, XXXI, XXXIII, and XLIV).

In addition, Nicholson published the first information about Rumi's "Discourses" (Fî-hi Mâ Fî-hi) in the English language (in a 1924 article in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society).1

Nicholson's work has been criticized for over-interpreting Rumi's Masnavi via the the theosophy of Ibnu 'l-`Arabi (teachings which Rumi, as well as his spiritual master Shams-i Tabriz, largely ignored); for deficiencies in understanding Persian idioms (he believed he would be a "more objective" scholar by never visiting or living in Middle Eastern countries); for over-prudishly translating "lewd" words and phrases in the Masnavi into Latin (for example, in Book IV, line 511:

"Materterae si testiculi essent, ea avunculus esset: this is hypothetical-- 'if there were.'" ["(If) an aunt [khâla] were to have testicles [khâya], she would be an uncle [khâlû]-- but this 'if there were' is (only) by supposing (something)."]); and for choosing a method of translating the Masnavi that was aimed primarily at helping gradutate students learn classical Persian (thereby making the translation and commentary even more difficult for the general reader to approa

ch and appreciate).

The present author (Ibrahim Gamard) has translated Nicholson's Latinized translations from Persian (with the help of several scholars, including a Latinist). And he has corrected Nicholson's English translation using the latter's indices of corrections (following the translation of Books III and IV). These indices bring

Nicholson's translation of Books I, II, and the first third of Book III into allignment with the oldest manuscript of the Masnavi in the world (a copy of the one owned by Husâmu 'd-dîn Chalabî, copied in 1278 CE--five years after Mawlânâ Rûmî's death). Nicholson made these lists of corrections because he did not obtain his own copy of the oldest manuscript until he had translated (and edited the Persian text of) about of a third of the Masnavi. In addition to this, the present author has made corrections that Nicholson made in his two volumes of commentary on the Masnavi (especially the places where he wrote: "Translate, instead..."). These improvements may be found on a new Masnavi website: MASNAVI.NET, regarding which the present author is a collaborator.

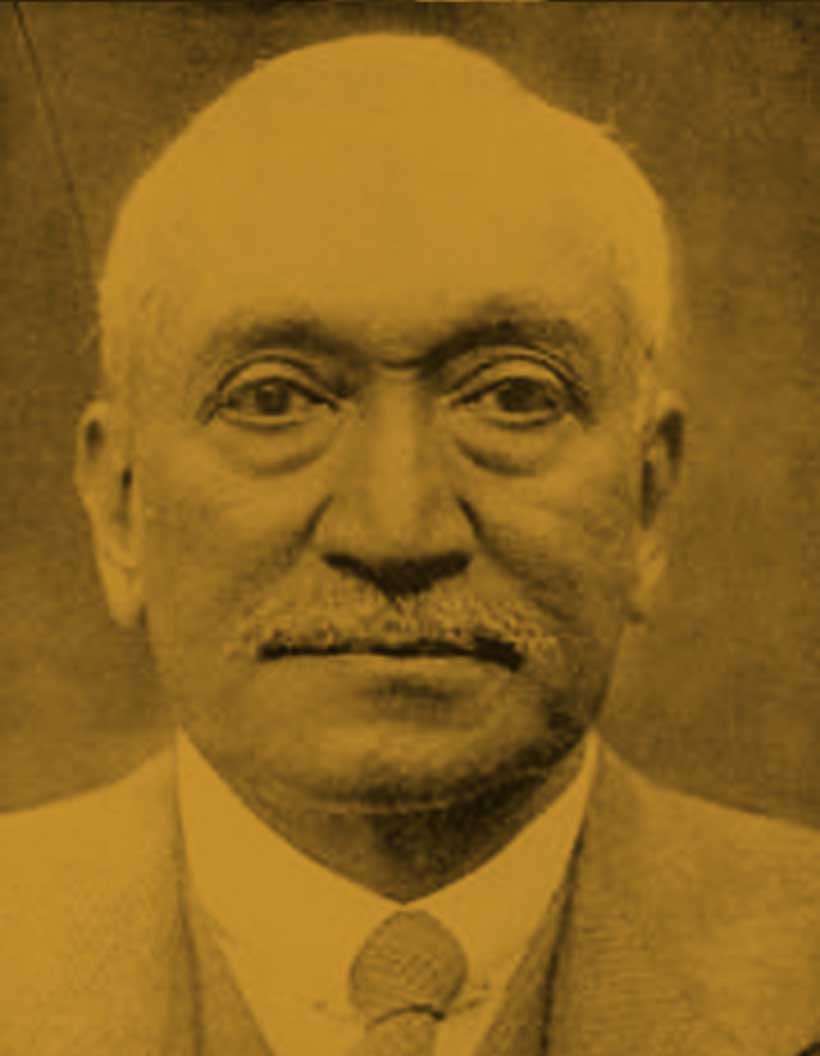

Ali was born in Bombay, British India, the son of Yusuf Ali Allahbuksh (died 1891), also known as Khan Bahadur Yusuf Ali, originally a Shi'i Isma'ili in the Dawoodi Bohra tradition, who later became a Sunni and who turned his back on the traditional business-based occupation of his community and instead became a Government Inspector of Police. On his retirement he gained the title Khan Bahadur for public service. As a child Abdullah Yusuf Ali attended the Anjuman Himayat-ul-Islam school and later studied at the missionary school Wilson College, both in Bombay. He also received a religious education and eventually could recite the entire Qur'an from memory. He spoke both Arabic and English fluently. He concentrated his efforts on the Qur'an and studied the Qur'anic commentaries beginning with those written in the early days of Islamic history. Ali took a first class Bachelor of Arts degree in English Literature at the University of Bombay in January 1891 aged 19 and was awarded a Presidency of Bombay Scholarship to study at the University of Cambridge in England. A. Yusuf Ali, 1911 (Text & Photo :Wikipedia)

Reynold Alleyne Nicholson (1868-1945), was the greatest Rumi scholar in the English language. He was a professor for many years at Cambridge Universtiy, in In the notes to this copy of the Quran’s translation, Abdullah Yusuf Ali writes, “The first Muslim to undertake an English translation was Dr. Muhammad ‘Abdul Hakim Khān, of Patiala, 1905. Mīrzā Hairat of Delhi also published a translation, (Delhi 1919): the Commentary which he intended to publish in a separate volume of Introduction was, as far as I know, never published. My dear friend, the late Nawwāb ‘Imād-ul-Mulk Saiyid Husain Bilgrāmī of Hyderabad, Deccan, translated a portion, but he did not live to complete his work. The Ahmadīya Sect has also been active in the field. Its Qādiyān Anjuman published a version of the first Sīpāra in 1915. Apparently no more was published. Its Lahore Anjuman has published Maulvi Muhammad ‘Alī’s translation (first edition in 1917), which has passed through more than one edition. It is a scholarly work, and is equipped with adequate explanatory matter in the notes and the Preface, and a fairly full Index. But the English of the Text is decidedly weak, and is not likely to appeal to those who know no Arabic. There are two other Muslim translations of great merit. But they have been published without the Arabic Text. Hafiz Gulām Sarwar’s translation (published in 1930 or 1929) deserves to be better known than it is. He has provided fairly full summaries of the Sūras, section by section, but he has practically no notes to his Text. I think such notes are necessary for a full understanding of the Text. In many cases the Arabic words and phrases are so pregnant of meaning that a Translator would be in despair unless he were allowed to explain all that he understands by them. Mr. Marmaduke Pickthall’s translation was published in 1930. He is an English Muslim, a literary man of standing, and an Arabic scholar. But he has added very few notes to elucidate the Text. His rendering is “almost literal”: it can hardly be expected that it can give an adequate idea of a Book which (in his own words) can be described as “that inimitable symphony the very sounds of which move men to tears and ecstasy.” Perhaps the attempt to catch something of that symphony in another language is impossible. Greatly daring, I have made that attempt. We do not blame an artist who tries to catch in his picture something of the glorious light of a spring landscape.”

(born Marmaduke William Pickthall; 7 April 1875 – 19 May 1936) was an English Islamic scholar noted for his 1930 English translation of the Quran, called The Meaning of the Glorious Koran. His translation of the Qur'an is one of the most widely known and used in the English-speaking world. A convert from Christianity, Pickthall was a novelist, esteemed by D. H. Lawrence, H. G. Wells, and E. M. Forster, as well as a journalist, headmaster, and political and religious leader. He declared his conversion to Islam in dramatic fashion after delivering a talk on 'Islam and Progress' on 29 November 1917, to the Muslim Literary Society in Notting Hill, West London. Marmaduke William Pickthall was born in Cambridge Terrace, near Regent's Park in London, on 7 April 1875, the elder of the two sons of the Reverend Charles Grayson Pickthall (1822–1881) and his second wife, Mary Hale, née O'Brien (1836–1904).[2] Charles was an Anglican clergyman, the rector of Chillesford, a village near Woodbridge, Suffolk. The Pickthalls traced their ancestry to a knight of William the Conqueror, Sir Roger de Poictu, from whom their surname derives. Marmaduke William Pickthall, 1875 (Text & Photo :Wikipedia)

In 1928, Pickthall took a two-year sabbatical to complete his translation of the meaning of the Qur'an, a work that he considered as the summit of his

achievement.

Like any other Muslim scholar, Pickthall too maintained that the Qur'an being the word of Allah (SWT) could not be translated. He wrote in his foreword: "The Qur'an cannot be translated." Understandably he titled his work that he finally published in 1930 as The Meaning of the Glorious Koran (A. A. Knopf, New York 1930), declaring that it is a simply a meaning of the Message and not a presentation in English of the Arabic text. It was first by a Muslim whose native language was English, and remains among the two most popular translations, the other being the work of Abdullah Yusuf Ali.

The mission of 'translating' the Qur'an had preoccupied Pickthall's mind since he reverted to Islam. He saw that there was an obligation for all Muslims to know the Qur'an intimately. Even while serving as an imam in London in 1919, he often put aside the then available translations and offered his own in the course of his khutba.

His devotion to the Book - a "wonder of the world" - was profound and he noted that while he had great difficulty in remembering a passage in his native English, he could easily memorize "page after page of the Qur'an in Arabic with perfect accuracy." Pickthall warned against the danger of adoring the book rather than its content. He chided the Muslims to "keep the message always in your hearts, and live by it." In his introduction to the surahs, Pickthall has powerfully focused on the universality of Islam.

During the course of his translation, Pickthall consulted scholars in Europe, and as a conscientious Muslim he wanted to secure the approval of the most learned authority, the ulema of Al-Azhar in Egypt. Towards this end, he traveled to Egypt in 1929 and stayed in Cairo for three months where he had the support of Rashid Rida. Some scholars suggested that the king reportedly believed that translating the Qur'an was a grave sin and any one aiding Pickthall could be

dismissed from Al-Azhar. Pickthall brushed aside their various suggestions and continued consulting the Al-Azhar scholars.

. E. Bosworth in his Encyclopedia of Islam says that Pickthall was "familiar with European Kur'an criticism, which he accepted and applied selectively.

Allen and Unwin published Pickthall's work under license from Knopf in England in 1939. Later, Pickthall completed an edition of his translation with

corresponding Arabic text (mushaf) within days of his final departure from India. This bilingual edition was first published in two volumes by the Government Press in

Hyderabad. Allen and Unwin also took over this edition in 1976. In 1953, the English text was issued in New York as a paperback in the New American Library.

Pickthall's translation itself has been translated. In 1958 extracts were put into Turkish by (inasi Siber) in Ankara. Other extracts were published by M. Cevki Alay and Ali Kitabo in Istanbul the same year. In 1964 it was rendered into Portuguese in Mozambique and in 1960 a trilingual edition - English, Arabic and Urdu -

appeared in Delhi. It has also appeared in Tagalog, the language of the Moro Muslims in the Philippines.

In 1982, in response to criticism by a Pakistani scholar, Pickthall's translation was scrutinized by the Islamic Ideological Council of Pakistan and found to be a

satisfactory translation. Earlier, his successor as editor of Islamic Culture, Muhammad Asad produced a new translation of the Qur'an after expressing dissatisfaction over Pickthall's knowledge of Arabic. Similarly, Professor Ahmed Ali of Pakistan prefaced his translation that he had undertaken the work to correct Pickthall's "errors".

In early 1935, Pickthall, just shy of sixty, retired from the Nizam's service and returned to England. In 1936 he moved to St. Ives where he died on May 19, 1936 and was buried in the Muslim cemetery at Brookwood, Surrey, near Woking on May 23. Later another illustrious translator Abdullah Yusuf Ali was to join him in this earthly domain.

Perhaps the elegy published in Islamic Culture summed up this illustrious life that Muhammad Marmaduke Pickthall was a "Soldier of faith! True servant of Islam!"

https://www.islamicity.org/1678/muhammad-marmaduke-pickthall-in-service-of-islam/

Barks is a private person who avoids admirers and the curious. “One appointment ruins the day,” he explains in his gentle Tennessee accent. “I love having nothing to do.” His initial wariness gives way to animation as he takes me on a tour of the place, which has the feel of a bachelor’s lair, with its big bed and large-screen television in the windowless downstairs.

This is the house that Rumi built. Born eight centuries ago this year, the Persian mystic is now one of the best-selling poets in the United States. That astonishing fame is due in large part to Barks, who has spent much of the past thirty years rendering thousands of Rumi’s poems into an English that captures the deep humanity and sublime divinity of the poet’s verse.

A poet in his own right who has published six books of poetry, Barks taught literature at the University of Georgia for thirty years before retiring. His journey with Rumi began in 1976, when friend and fellow poet Robert Bly gave him a copy of a stilted academic translation of Rumi’s poetry. “These poems need to be released from their cages,” Bly said. Barks had never heard of Rumi, and he did not speak or write Farsi (nor does he now), but he accepted the challenge, using existing translations and his own poetic talents. That work led him to Philadelphia, where he became a student of Sri Lankan spiritual teacher Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, who provided Barks with a living example of Sufism, the mystical Islamic tradition of which Rumi was an adherent. All Muslims believe they will be reunited with God after death, but Sufis use esoteric practices to encounter the ineffable in this life. Barks’s Rumi project eventually grew into a series of books — now numbering nineteen — that shocked publishers by catapulting a thirteenth-century Persian poet onto the bestseller lists. It’s no small irony that a Persian Muslim is one of America’s most popular poets at a time when relations between the U.S. and Iran — and the Islamic world as a whole — are so strained.

Jelaluddin Rumi was born September 30, 1207, in the ancient trading city of Balkh in what is now Afghanistan, during a time of war, social upheaval, and spiritual questioning. In the West, Thomas Aquinas, Meister Eckhart, and Saint Francis of Assisi were remaking Christianity; in the Holy Land, Europeans were fighting Muslims; and in the East, the medieval world of Islam was at the height of its intellectual and artistic vigor. When Rumi was five, his father took his family west to avoid Mongol invasions, passing through the great city of Baghdad before settling at Konya in what is now Turkey. When Rumi was thirty-nine, he met the mysterious Shams, an older mendicant who was to have a profound influence on Rumi’s life and work. Legend has it that Rumi and Shams first met beside a fountain in Konya. Rumi was talking to his students with his father’s spiritual notebook, the Maarif, open beside him. Shams apparently interrupted the conversation by pushing the precious text into the water. When Rumi demanded to know why Shams had done this, Shams reportedly replied, “It is time for you to live what you have been reading of and talking about.”

This was the start of a passionate friendship between the two men. At one point Shams disappeared — or, some say, was killed by Rumi’s jealous followers.The brokenhearted Rumi ultimately composed forty-five thousand verses in honor of his lost friend. He also produced works of theology and philosophy, including the massive six-volume Masnavi, which is called the “Persian Koran” for its lyricism and wisdom. Rumi died in his bed in Konya on December 17, 1273.

Barks’s interpretations of Rumi sometimes irritate both liberal academics and conservative Islamic theologians, who say he has catered to a New Age market by downplaying the religious and patriarchal aspects of the poet’s huge corpus in favor of the universal and the sensual. Most scholars, however, give Barks credit for breathing life into poems that are notoriously difficult to translate into readable English, and for making Rumi virtually a household name in the West.

Barks has a grizzled beard and wavy eyebrows, and he drives a pickup truck. There’s little of the media star about him, despite the fact that his books of Rumi’spoetry have sold more than three quarters of a million copies, earning him the attention of everyone from Iranian imams to journalist Bill Moyers. Rumi’s poetry, Barks writes, “is God’s funny family talking on a big, open radio line. BY ANDREW LAWLER • OCTOBER 2007

https://www.thesunmagazine.org/issues/382/walking-around-in-the-heart